Assessment of Dementia Patients in the Emergency Department - #72

Take QuizAssessing delirium in dementia patients in the emergency room

- Identify, understand, and support the patient-caregiver “dyad”.

The patient-caregiver dyad is the unit of assessment and management for patients with dementia, especially for patients with live-in family caregivers.

Caregivers must navigate a confusing, fragmented care system, often without assistance, while providing continuous care for their loved one. The ED visit is an opportunity for social work consultation and/or providing a caregiver support resource that includes information on medical, home-based, and community resources. Emergency Department (ED) presentation may signal that the patient can no longer be cared for in their current situation without additional support.

(A) Dementia changes the caregiver-patient relationship over time, placing increasing emotional, physical, social, and financial demands on the caregiver. Ask the caregiver about changes in their ability to provide care, recent changes in the patient’s functional dependence, and how these relate to the current ED evaluation.

(B) Behavioral and psychologic symptoms of dementia (BPSD) are a major source of caregiver burden and a frequent reason for seeking emergency care.

- Apathy, depression, personality changes, aggression, and resistance to care.

- Sleep cycle disturbances.

- Psychotic symptoms (suspicion, paranoia, delusions, hallucinations).

- Wandering, pacing, exit seeking, and repetitive activities (perseveration).

- Communicate that BPSD are involuntary expressions of the disease. The belief that these behaviors are volitional is identified as a major source of caregiver burden.

2. Tailor your assessment strategy to the communication needs of patients with dementia.

Dementia erodes the ability to receive and express verbal communication, creating frustration if not recognized by the provider. Patients maintain the ability to interpret nonverbal communication.

(A) Practical communication strategies include:

- Introduce yourself to the patient and caregiver, using the patient’s preferred name.

- Adopt a calm, unhurried approach with minimal interruption.

- Ask specific, closed-ended questions and repeat or rephrase as necessary.

- Be aware of nonverbal cues of facial expression, body language, verbal tone and cadence.

(B) Assessing pain is challenging in patients with limited verbal ability. The Pain Assessment in Advance Dementia (PAINAD) scale recommends observation of breathing, negative vocalization, facial expression, body language, and consolability.

3. Contextualize the acute presentation with a comprehensive history from ancillary sources.

Constructing an accurate history often requires that members of the ED team contact the nursing facility, caregivers, referring providers, and pharmacies. Seek to understand “What has changed today?” and the caregiver’s “Biggest Worry”. Address these issues on initial evaluation to align the patient’s needs with an efficient ED evaluation and disposition.

(A) Document baseline cognitive and functional status including rapidity and extent of decline.

(B) Consider the level of assistance required. A different level of function is required to reside in Assisted Living, Acute or Subacute Rehabilitation, or Long Term Care.

(C) Screen for neglect, self-neglect, and abuse. Cognitive impairment and functional dependence are major risk factors for neglect and abuse.

4. Adverse medication events are common, both as contributing factors to an acute presentation and in the ED setting.

Seek to identify which medications are actually taken by the patient (e.g., ask patient/caregiver, inspect pill bottles, review facility records, call the pharmacy).

(A) Evaluate for adverse medication events by considering: new medications, dose adjustments, and abrupt cessation; changes in adherence; medication interactions.

- Consult the “Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults” to inform the risk of an adverse drug event, and when considering medications to administer. Avoid, if possible, the use of anticholinergic, benzodiazepine, H1-receptor antagonist, sedative/hypnotic, and anti-psychotic medications. Consider non-systemic analgesia, such as regional nerve blocks or topical agents, in treating musculoskeletal pain.

5. Anticipate, understand, and safely manage “distressed behaviors” and resistance to care.

Patients with dementia may respond to the ED environment and/or their underlying emergent condition with agitation or aggression. These behaviors may be a response to an unmet need.

(A) Consider the A/B/C (Antecedents/Behavior/Consequences) approach to interpreting distressed behavior, with attention to addressable causes.

- Patient- pain, medication causes, metabolic derangement, constipation, urinary retention, incontinence.

- Caregiver- interactions between the patient, caregivers, and ED team.

- Environment- temperature, noise, light, overstimulation, absence of familiar caregiver.

(B) Begin with nonpharmacologic approaches to distressed behaviors.

- Address unmet needs. Form a therapeutic alliance with the patient and caregiver and assigning trained staff or volunteers to attend the patient.

(C) Medications are indicated when there is a safety risk for the patient or providers.

- Low dose typical (haloperidol) or atypical antipsychotics are preferred to benzodiazepines in treating dangerous aggression and/or psychotic symptoms.

- Avoid typical and atypical antipsychotics with strong D2 receptor antagonism (olanzapine and risperidone) in patients with Lewy Body Dementia or Parkinson’s disease due to the risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome, parkinsonism, somnolence, and orthostatic hypotension. Consider quetiapine in this population.

6. Assess medical decision-making capacity and locate a surrogate decision maker and advanced directive early in the ED course.

A diagnosis of dementia does not necessarily infer decisional incapacity. Consider the CURVES mnemonic for assessing medical-decision making capacity.

(A) Choose and Communicate – can the patient communicate a choice?

(B) Understand- Does the patient understand the risks, benefits, alternatives, and consequences of the choice?

(C) Reason- Is the patient able to provide a logical explanation for the choice?

(D) Value- Is the choice consistent with their value system?

(E) Emergency- Is there an imminent, serious risk?

(F) Surrogate- Is there a surrogate decision maker available?

7. Screen for delirium.

Delirium is a form of acute brain failure that occurs in approximately 10% of older ED patients and has been associated with higher mortality rates. Delirium in the demented patient leads to an acute decline in performance and mental status. While it may be mistaken as rapidly progressing dementia, delirium may be more reversible.

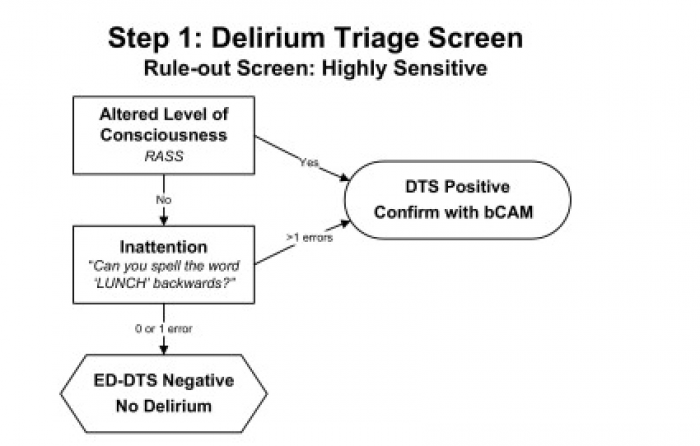

(A) The ED Delirium Triage Screen (ED-DTS) is a brief (<20 second) tool designed to be highly sensitive and integrated into an ED RN triage assessment. A negative ED-DTSW would rule out delirium whereas a positive ED-DTS would trigger a more formal delirium assessment.

(B) The Confusion Assessment Methodology (CAM) is a follow-up tool to more fully assess the presence of delirium. See GFF #46 Assessment and Prevention of Delirium in the ICU for more information.

Evaluation of dementia patients in the emergency department.

Perform an efficient and effective evaluation of a dementia patient in the emergency department.

An estimated 5.5 million Americans are living with dementia, with the disease affecting approximately 10% of adults over 65 years.

Science Principles

- Master dementia –specific diagnostic considerations in the assessment of a patient with dementia in the emergency department.

- Assess the bio-psycho-social needs of an older adult with dementia in the emergency department.

Review of Systems (ROS)

Geriatric Topics

ACGME Compentencies

Science Principles

- Bejjani, C, et al. Addressing Psychiatric Problems of Dementia in the Emergency Room. Internet J Emer Med. 2012:7:(2).

- Chow, Grant, et al. CURVES: A Mnemonic for Determining Medical Decision-Making Capacity and Providing Emergency Treatment in the Acute Setting. Chest;2010:137:2:421-27.

- Clevenger, C, et al. Clinical Care of Persons with Dementia in the Emergency Department: A Review of the Literature and Agenda for Research. JAGS.2012:60(9)1742-1748.

- Emergency Room Treatment of Psychosis. Lewy Body Dementia Association, Inc. 2016. https://www.lbda.org/go/er.

- Han, Jin H., et al. "Diagnosing delirium in older emergency department patients: validity and reliability of the delirium triage screen and the brief confusion assessment method." Annals of emergency medicine 62.5 (2013): 457-465.

- LaMantia, M, et al. Emergency Department Use Among Older Adults with Dementia. Alz Dis Assoc Disord. 2016:30(1)35-40.

- LaMantia, Michael A., et al. "Screening for delirium in the emergency department: a systematic review." Annals of emergency medicine 63.5 (2014): 551-560.

- Sadavoy, J, et al. Refining Dementia Intervention: The Caregiver-Patient Dyad as the Unit of Care. Can Ger Soc J of CME:2012;2(2)5-10.

- Sikka, V, Psychiatric Emergencies in the Elderly. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2015;33(4)825-39.

- Warden V, et al. Development and Psychometric Evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale. J AM Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4(1):9-15